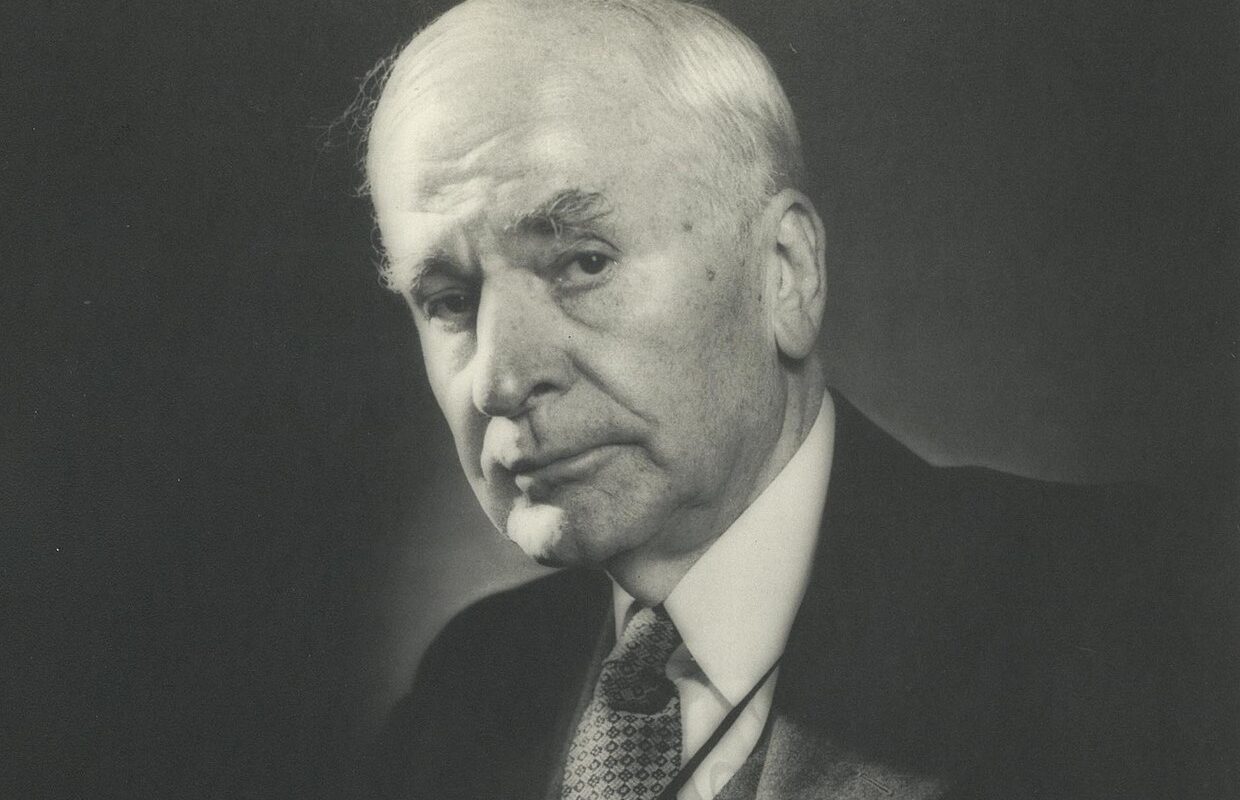

Cordell Hull fut le secrétaire d’État des États-Unis entre 1933 et 1944 dans l’administration du président Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Voici ses souvenirs autour du ralliement de Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon à la France Libre.

The Memoirs of Cordell Hull, Volume 2

The Memoirs of Cordell Hull, Volume 2

Macmillan Company, 1948 (1804 pages)

At that very moment our informal relations with De Gaulle were embittered by his unwarranted action in ordering the forcible occupation of the French islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, off the Newfoundland coast, by Free French forces. The incident occurred on Christmas Eve while the President was entertaining Mr. Churchill at the White House.

These islands had been under the jurisdiction of Governor Robert at Martinique. We had already reached agreements with Admiral Robert, renewed a few days after Pearl Harbor, whereby our interest in maintaining the status quo of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon was safeguarded. We had also had negotiations with Canada during November and December concerning a powerful wireless station on Saint-Pierre which both Canada and we feared might serve as a guide to German submarines. We agreed that Canada should send operators to supervise messages transmitted by the station and that we would join Canada in economic pressure against the islands if the local governor refused to accede to Canada’s move.

The Canadian Government had informed us on December 4 of a suggestion from the British Government that the islands be occupied by the Free French. This suggestion did not appeal either to the Canadians or to ourselves. For my part, I looked with something like horror on any action that would bring conflict between the Vichy French and the Free French or the British. […]

At the end of November, De Gaulle had sent his « Minister of Marine, » Admiral Muselier, to inspect the Free French corvettes operating with the British off Newfoundland and at the same time to undertake to rally the Saint-Pierre-Miquelon islands to his movement. Muselier went to Ottawa where he sought the opinion of the Canadian Government. The Canadian External Affairs Department would not give him permission. […]

Muselier saw our Minister in Ottawa, Pierrepont Moffat, that same day and asked for the opinion of the American Government as to a land-ing of Free French troops on the islands. The President read Moffat’s telegram to this effect and said he did not favor any policy whereby the Free French were permitted to move in on the Saint-Pierre and Miquelon situation. This was telephoned to Moffat.

Moffat informed Muselier of our views on December 16. Muselier said to Moffat he felt we were making a mistake, but he would accept this decision.

The Counselor of the Canadian Legation in Washington, Mr. Hume Wrong, informed the State Department on December 2 2 that, since the British Government did not « go along » with the policy suggested in the American-Canadian discussions for action by Canada to supervise the radio station at Saint-Pierre, the Canadian Government was not going ahead with its proposed action. Wrong said, however, he could inform us that any action by the Free French forces had been called off.

Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King stated to Minister Moffat on the same day that he agreed with the decision of the United States and felt that any slight advantages of action by the Free French in occupying the islands would be outweighed by the bigger issue involved, which he said he understood. Meantime, however, Muselier had communicated with De Gaulle, who ordered him to go ahead just the same. Without previous warning to Canada or the United States, Admiral Muselier therefore landed a small force on the islands on Christmas Eve and took charge. Our Consul at Saint-Pierre, Maurice Pasquet, re-ported to us on December 26 that Muselier was much aroused against De Gaulle whom he accused of having acted as a dictator. Muselier said be intended to resign in protest against the unilateral order given him by De Gaulle without the prior approval of the United States and Canada. Sometime later Muselier did break with De Gaulle. British Ambassador Halifax came to see me Christmas afternoon to inform me on behalf of the Foreign Office that the British Government disclaimed all responsibility for the Free French action and that Muselier had acted contrary to the instructions of the Foreign Office. Minister Moffat reported to me from Ottawa that the Canadian Government was « shocked and embarrassed » by the incident and regarded it as « so close to a breach of faith that it cannot fail to embarrass their future relations with the Free French. »

On that Christmas Day I issued a statement, with the approval of the President, characterizing the incident by three « so-called Free French ships » as « an arbitrary action contrary to the agreement of all parties concerned and certainly without the prior knowledge or consent in any sense of the United States Government. » I said we had inquired of the Canadian Government as to the steps Canada was prepared to take to restore the status quo of the islands. Comparatively unimportant though the islands were, their forcible occupation by the Free French was greatly embarrassing to us for several reasons. It might seriously interfere with our relations with Marshal Petain’s Government.

Only eleven days before the occupation the President had sent a message to Petain, following Vichy’s proclamation of neutrality, in which he gave « full recognition to the agreement reached by our two Governments involving the maintenance of the status quo of the French possessions in the Western Hemisphere. » Moreover, we had just renewed an agreement with Admiral Robert at Martinique on this subject. And, finally, the American Republics had agreed at the Havana Conference to oppose the transfer of sovereignty, possession or control of any territory in the Western Hemisphere held by European Powers. Admiral Robert quickly informed us that in his opinion the United States was « obligated to obtain the reestablishment of French sovereignty over Saint-Pierre-Miquelon. » And Admiral Leahy cabled me from Vichy that Admiral Milan informed him that the Germans immediately used De Gaulle’s seizure of the islands as an argument for the entry of Axis troops into French North Africa so that they might protect it against a similar invasion.

Unfortunately, many influential people, both in the United States and abroad, did not comprehend these broader issues, and unleashed a violent attack on the State Department and on me for having issued the statement I did on the seizure of the islands. Few actions that seemed so minor have ever aroused opposition that became so bitter. In the weeks that followed, the State Department, with myself as its chief, became the target of editorials, radio attacks, and representations from various organizations, although the President had given his full approval to our reaction. A special offensive was launched against us because of the word ((so-called » in the phrase « so-called Free French ships » in the statement. Our attackers thought that with this word we were questioning the existence of the Free French or the fact that they were free, whereas by the phrase we simply meant: three ships supposedly of the Free French.

I sought to work out with Lord Halifax and with French Ambassador Henry-Haye a speedy settlement of the controversy. To Halifax on December 26 I suggested it might well be possible to get an agreement with Governor Robert at Martinique, approved by Vichy, to allow three or four Canadian experts to supervise messages passing over the radio station at Saint-Pierre. Thereupon the British Government could request the Free French to withdraw from the islands; and Britain and Canada, in order to give De Gaulle a face-saving way out, could then praise very highly the part the Free French occupation had taken in securing the agreement for supervision. […] He agreed to my discussing with Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King a proposed agreement with Vichy France and to our then asking Prime Minister Churchill to request De Gaulle to remove his forces from the islands. After I talked at length the following day with French Ambassador Henry-Haye, he said he would recommend earnestly to his Government and to Governor Robert a settlement that would either involve shutting down the wireless station at Saint-Pierre, with a Canadian guard over it, or permitting two or three Canadians, along with an American attached to the consulate, to supervise the operation of the station. When I informed the Ambassador that the Governor of the islands had made himself personally offensive to Canada and to some of the people on the islands, and that it was desirable he should be replaced, Henry-Haye said he would undertake to see that this was done. Three days later he brought me the reply of his Government. Vichy left the settlement of the matter to Governor Robert, but stated with dramatic emphasis its claim to sovereignty over the islands. Henry-Haye himself launched into a loud monologue about French sovereignty and about France being a great country and having to be treated accordingly. I interrupted him by saying: « At a moment when I’m being subjected to every sort of abuse, even in this country, as I try to safeguard the whole situation by friendly settlement, just and fair to all, the only reply I receive from you is a stump speech about the greatness of the French nation. Soon it will be too late to handle this matter on its merits and in a proper spirit because of its explosive possibilities. » Henry-Haye promised to take the question up with his Government again. The previous day Lord Halifax had come to tell me that his Govern-ment was very fearful of injuring the De Gaulle movement in Africa if it should resist De Gaulle’s desire to hold on to the islands. I had a blunt conversation with Prime Minister Churchill at the White House on the whole question of our relations with Vichy France, with the seizure of the islands as a springboard. The President, who thor-oughly agreed with my position, was present at this discussion, but he remained on the side lines while Mr. Churchill and I indulged in some plain speaking. I pointedly accused De Gaulle of being a marplot acting directly contrary to the expressed wishes of Britain, Canada, and the United States, and I asked the Prime Minister to induce him to withdraw his troops from the Saint-Pierre and Miquelon islands, with Canadians and Americans assuming supervision over the radio station at Saint-Pierre. Mr. Churchill said that if he insisted on such a request his relations with the Free French movement would be impaired. I replied that the presence of the Free French on the islands, without our doing anything about it, jeopardized our relations with the Vichy Government. I reemphasized the importance of continuing those relations in that they enabled us to use our influence to keep the French fleet and bases from falling into German hands and to keep observers in Vichy France and in French North and West Africa. I said it was unthinkable to me that all these benefits to the British and American Governments should be junked and thrown overboard in order to gratify the desire of the De Gaulle leaders. Mr. Churchill agreed that these relations with Vichy were important to Britain as well as to the United States. I directly asked the Prime Minister whether he could not do something to prevent De Gaulle’s movement from continuing its radio and press attacks on the American Government. I said that, since these attacks were made from London and continued unchecked, the impression was being created that Britain approved them or acquiesced in them. When the Prime Minister wondered whether he would be in position to exercise any such censorship over De Gaulle, I said that De Gaulle’s propaganda campaign against us was being financed by British funds, and De Gaulle could be quickly stopped dead in his tracks if Mr. Churchill threatened to withdraw Britain’s subsidies.

Mr. Churchill agreed to consider the various points I had raised. Matters were at this point when the Prime Minister went to Ottawa and there on December 3o delivered a violent diatribe against Vichy along with fulsome praise of De Gaulle. Coming at a moment when public agitation over the seizure of the Saint-Pierre and Miquelon islands and over our reaction to it was so rabid, it gave a popular impression that the Prime Minister was approving De Gaulle’s action. At the same time it was an implied condemnation of our continued diplomatic relations with any Government so base and despicable as his description of the Vichy group. And yet, only nineteen days before, on December i t, Mr. Churchill, as the « former naval person, » had sent the President an important cable with a very different approach to the subject. Referring to reports that Admiral Leahy was leaving Vichy to return to the United States, he said he was most anxious to discuss with the President a project of offering Vichy « blessings or cursings, » following a British victory in Libya, and he then added: « Trust your link with Main will not be broken mean-while. We have no other worth-while connection. » The day after Mr. Churchill’s speech, I sent the President a memorandum in which I said: « Our British friends seem to believe that the body of the entire people of France is strongly behind

De Gaulle, whereas according to all my information and that of my associates, some 95 per cent of the entire French people are anti-Hitler, whereas more than 95 per cent of this latter number are not De Gaullists and would not follow him. This fact leads straight to our plans about North Africa and our omission of De Gaulle’s cooperation in that connection. » Regarding this last point, the President had early determined that De Gaulle would not be included in any plans for an Anglo-American expedition to French North Africa, and he emphasized this determination to Mr. Churchill. He felt that inclusion of De Gaulle might prejudice the secrecy of the plans and would automatically produce resistance from the French in North Africa.

In the same memorandum I summed up the Free French seizure of the islands by saying: « It is a mess beyond question, and one for which this Government was in no remote sense responsible. » I remarked that it might lead to « ominous and serious developments. »

Mr. Churchill returned to Washington almost immediately after his Ottawa speech. I saw him at the White House on January 2 and did not hesitate to say that his remarks about Vichy and De Gaulle were « highly incendiary » and had brought far-reaching injury to me and to the State Department. I pleaded with him that, since our relations with Vichy were of great value to Britain as well as to the United States, as he himself had repeatedly acknowledged to us, it would be of wonderful assistance to us if he could say « just a few little words » to the effect that, although Britain had not desired to maintain relations with Vichy, those maintained by the United States were worth while in the common cause. Otherwise, I said, the existing general impression that the United States was « appeasing » Vichy, in direct violation of British wishes, would continue and spread. The Prime Minister was not cordial to the suggestion.

I then asked the President to bring his own personal influence with Churchill to bear to produce a straightening out of this anomalous situation. Mr. Roosevelt, however, said he had done what he could and he could not do anything further. These attitudes of the President and the Prime Minister were in striking contrast to their later attitudes when they both became bitterly hostile to De Gaulle, and remained so.

When I returned to the State Department I had several of my assistants draw up a draft statement that might be issued by the President and the Prime Minister. This I sent to the President the same day, with a memorandum in which I said it was designed « to quiet steadily spreading rumors and reports very damaging to the British-American situation. » I said I had just talked with the French Ambassador. « I went after him very strongly, » I said, « about simply closing down the [Saint-Pierre] wireless station and agreeing for a Canadian citizen to be about the premises at all times to see that it is kept closed down, and also to change governors—all of this to be done if and as the Free French who are occupying the islands make their departure, thereby restoring the status quo. » […]

Speaking as I had seldom spoken to the representative of a friendly nation, I said: « I wonder whether the British are more interested in a dozen or so Free Frenchmen, who seized these islands, and the capital they can make out of it primarily at the expense of the United States Government, than they are in Singapore and in the World War situation itself. I have neither seen nor heard of anything from British spokesmen in the last few days that would indicate to me that there existed a World War compared with the Saint-Pierre-Miquelon situation. »

What heightened our exasperation over the Saint-Pierre-Miquelon incident was this very fact that De Gaulle should have so recklessly plunged into an adventure eminently calculated to disturb relations among the United States, Britain, and Canada, and that Britain should have been so reluctant to redress the damage done at the precise moment when the Japanese were driving the Western Powers out of the Orient, slashing into Malaya, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies, threatening Australia, and inflicting defeat after defeat on the Occidental forces, while the wreckage of the American Navy listed at crazy angles in Pearl Harbor, The President agreed to my proposed solution. We thereupon submitted it to Mr. Churchill. He accepted it on condition that De Gaulle agreed. Meantime the Petain Government agreed to it. But De Gaulle rejected it. I was thereupon informed that Mr. Churchill, then in Ottawa, cabled De Gaulle in London that the United States would send warships to the islands to expel the Free French.

After Mr. Churchill returned to London he informed the President on January 23 that he had had a « severe conversation » with De Gaulle on January 22. Previously De Gaulle had said to Eden that he would agree to the issuance of a communiqué to straighten out the matter provided all parties agreed to three secret points that would not be mentioned in the communique. These were that the Free French administrator would remain on the islands but be merged in a consultative council, that the marines should remain on the islands, and that the council would be under the orders of the Free French National Committee. The Prime Minister informed the President that De Gaulle agreed not to insist that his secret points be accepted. De Gaulle, however, never did consent to our proposed agreement which would have ironed out the dispute. Mr. Churchill said in his cable to the President that he did hope that the solution for which he had worked « would be satisfactory to Mr. Hull and the State Department. I understood fully the difficulty in which they were placed. »

Finally, as the turmoil over the incident declined, I felt that the wisest course would be to let the matter rest until the end of the war. I so recommended to the President in a memorandum on February 2, 1942. I repeated to him that I had been greatly preoccupied throughout the incident lest the Vichy Government should be outraged, for the simple but compelling reason that I still hoped to hold Vichy to its assurances concerning the French fleet, colonies, and bases. The President agreed with my recommendation, and a matter that had threatened to become a whole chapter in history accordingly declined to a footnote.

Our relations with De Gaulle’s movement were not helped by the incident. There was no doubt in the minds of the President or myself that De Gaulle personally was responsible for violating his commitment to Britain and for going directly contrary to the wishes of the United States and Canada. We regarded him as more ambitious for himself and less reliable than we had thought him before. As for myself, the refusal of the President to bring more pressure on Mr. Churchill to clarify the relations between Great-Britain and the United States with regard to De Gaulle and Vichy was one of several factors that almost caused me to resign as Secretary of State in January, 1942. I so seriously considered taking this step that I penciled out a note to the President tendering my resignation.

My principal reason for almost resigning was the state of my health. In this note I pointed out that I had to give serious attention to conserving my health. I recalled that during the first half of the previous year, 1941, I had been hopelessly overworked and had been obliged to take a long rest.